9/22/2024

Theatre and the Novel

This is number eighty in the blog series, “My Life in Erotica.” I encourage you to join my Patreon community to support my writing.

IT WILL COME AS NO SURPRISE to some of my readers that my education was not specifically in writing. My double major in college included English, but my real focus for my BA and graduate studies was theatrical design with a secondary emphasis on play writing.

While I did my master’s work in Minnesota, I designed and built 24 shows in 24 months and had two of my plays produced. Hooray for teaching assistantships. I ended 1978 in a state of total burn-out. I left my job, my marriage, theatre, and almost everything else in my life. I decided, eventually, to go into something low-stress.

Like publishing.

Ah, well.

Nonetheless, I carried a huge amount of theatrical training into writing and publishing. One of the things that has stuck with me through the years is simply that Friday night at 8:00 the curtain goes up. There comes a point with every novel at which it has to be released to the audience, even if the leading actress is still being sewn into her costume! It’s showtime!

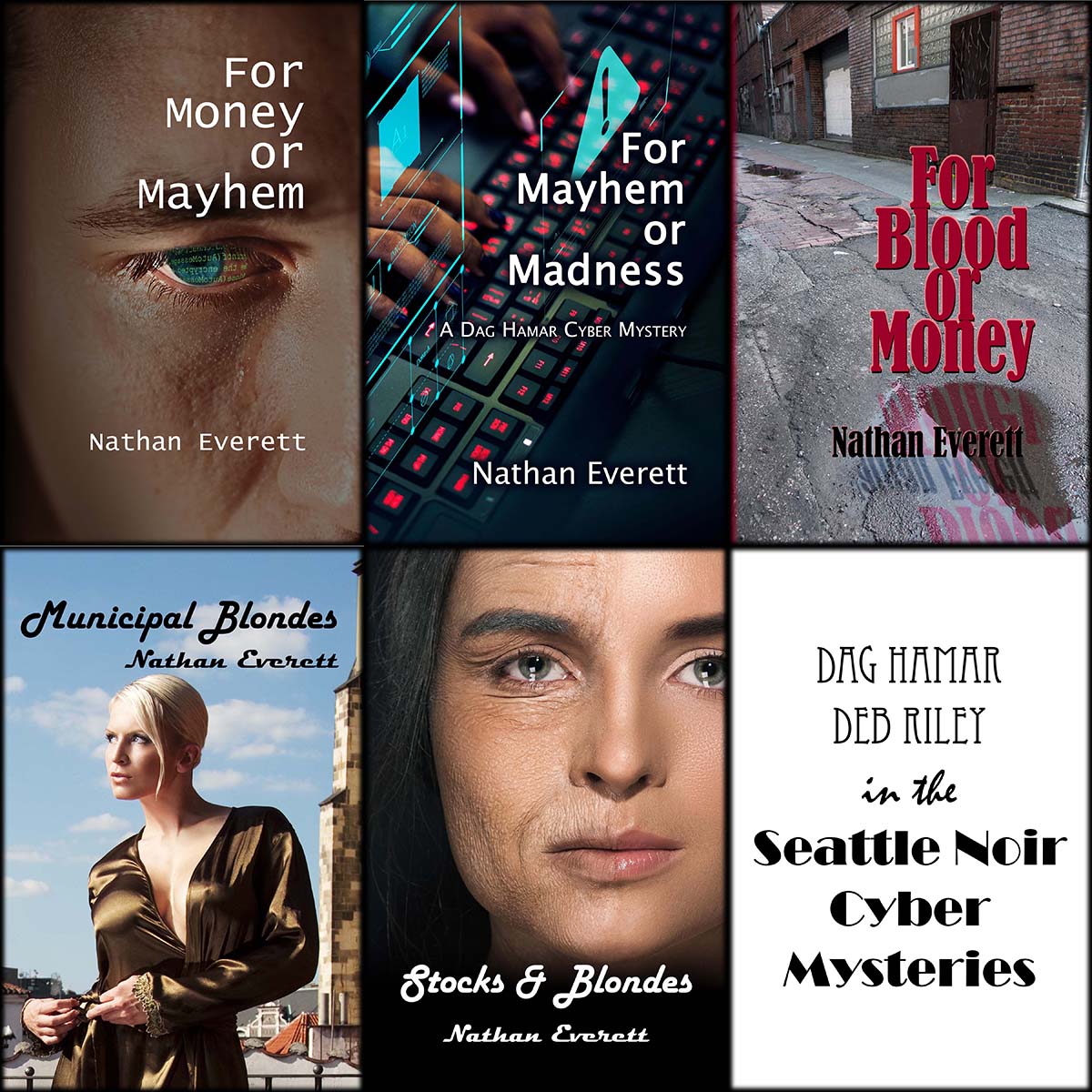

This is a good time to mention that books are not necessarily written in chronological order. The first Nathan Everett book published by Long Tale Press in 2007 was For Blood or Money. I always planned to continue this as a series, so I wrote the next two volumes, Municipal Blondes and Stocks & Blondes, in the next two months after I finished the draft of For Blood or Money. But they weren’t published until much later!

Instead, I went back and wrote the first book in the series, For Money or Mayhem. Eventually, I wrote the second book in the series, For Mayhem or Madness. Then I published the final two that had been written years earlier. Confused yet? Maybe someday I’ll write other volumes in this popular cyber crime series.

But as my first published book, For Blood or Money had problems in it that I really needed to correct before I brought out the second edition in 2013 when I was ready to release For Money or Mayhem.

One of those problems was a theatrical no-no referred to as “Breaking the Fourth Wall.” If you look at the photo of my set for King Lear at the top of this post, you’ll readily see it is intended to be viewed from the front. Even though the stage breaks through the proscenium arch in order to accommodate a cast of dozens, there was still a fourth wall between the action and the audience.

Breaking the fourth wall involves crossing that boundary between the action and the audience. A character comes forward and talks directly to the audience members instead of staying on the stage.

The most typical way this is done in writing a novel is in the narrator using comments directed to the reader with words like, “You know…” or “If you take a pint…” We use these expressions all the time in speech when we are talking to other people. It is a kind of universal ‘you.’ But it seldom works in a novel unless you are specifically writing in a second person POV. In my humble opinion, that seldom works anyway. In a first person or third person story, it breaks the connection with the reader rather than enhancing it.

I think this is often done to try to heighten the personalization of the story, but it can often backfire… even in the character’s dialog. For example:

Dag: “Imagine your husband is cheating on you.”

Jen: “I’m not married.”

Dag: “Imagine a woman whose husband is cheating on her.”

Dag’s personalization of the hypothetical experience backfired on him. In the same way, if I use the pronoun “you” in my writing, I stop telling a story and attempt to personalize it by addressing the reader. That, except in rare occurrences, will also backfire. I did this a lot in For Blood or Money, and realized that it most frequently shows up in first person narratives.

The entire Seattle Noir Cyber Mysteries collection and the individual eBooks are available at Bookapy. Paperbacks are available online.

You will notice (See how easy that was?) that I break the fourth wall in this blog all the time. That is because I am not telling a story independent of the reader, but rather am telling you, the reader, what I’ve learned about writing and erotica over the years. Since this was not learned in a formal course on writing novels, the ideas sometimes are out of order and seemingly random. However, I find they help me in my writing as I dredge things up and review them in my current work.

Breaking the fourth wall is not unheard of in third person narratives, and is even more jarring. For example:

“He examined the contents of the bag and pulled out a pocket knife, a role of duct tape, and a ball of string. Then he reached for one more thing. You never know when chewing gum might come in handy.”

In the last sentence, I stopped telling a story and gave an aside to the reader. (I also switched tense!) That was the kind of thing I needed to correct in the Seattle Noir Cyber Mysteries and in everything else I write. My editors are also very good at spotting those things and reminding me to correct them.

Another lesson I learned from my time in theatre, was that plays are performed in a black box. The designer needs to give an indication to the audience regarding where the setting ends. Most proscenium settings do not have ceilings because the lights need to be directed downward in order to eliminate obnoxious shadows on the background. The tops of walls and edges of the set need to be defined so the audience knows where the action stops. “Nothing to see above here.” Above, my setting for Blithe Spirit shows where the set ends and the black box begins.

That is more difficult to apply to a novel, but I find it is necessary. I need to know where the edges of the story are. In dramatic works, especially tragedies, playwrights are still paying lip service to the concept of Aristotle’s three unities.

The action should be consolidated in a single plot. (Unity of Action)

The play should take place in one location. (Unity of Place)

The entire action should take place in a single daylight period. (Unity of Time)

Of course, these ‘rules’ were not dug from the extant works of Aristotle until the late 1500s, so there are many examples of plays from greats like Shakespeare that do not follow them at all. While Aristotle’s suggestion is way too limiting for a novel, it is still a good reminder to focus on a single major plot. A novel is typically vastly longer than a play, so the unities of time and place are not as strongly adhered to. But a conscientious writer will still know the boundaries of his story. This is the beginning, this is the middle, and this is the end.

I try, often unsuccessfully, to follow that pattern.

Did you know there are twelve defined tenses in the English language? I didn’t get around to talking about that this week, but next week I’ll tackle “Tense and Pretense.”

Please feel free to send comments to the author at devon@devonlayne.com.