9/8/2024

The Johari Window

This is number seventy-eight in the blog series, “My Life in Erotica.” I encourage you to join my Patreon community to support my writing.

“WHEN YOUR ONLY TOOL is a hammer, all your problems look like nails.”

That’s my rephrasing of an adage passed down through the sixties by the likes of Abraham Kaplan and Abraham Maslow. Kaplan referred to it as the law of the instrument. He says: “Give a small boy a hammer, and he will find everything he encounters needs pounding.”

I prefer to believe that all through the sixties, the underlying message was not to recognize different kinds of problems, but to expand your tool chest. Certainly, one might expand the uses of a hammer as well. Pull nails, act as a doorstop, be a murder weapon, weigh down a stack of paper, etc. But most of those could be accomplished by using a better tool.

Crime fiction novelist Raymond Chandler once said, “When in doubt, have a man come through a door with a gun in his hand.” I read a series of stories by a popular SOL author back in the days before I started writing erotica. This author was known for his cliff-hanger chapter endings. (Sorry, I can’t remember the name of the author.) This SOL author had taken Chandler’s advice literally and this scene popped up at the end of many chapters. An alternative was, “And then the phone rang.” Or, “Headlights flashed through the window.” The interruption to an action sequence that was really going nowhere in a story that had no end was the interpretation for this author.

When you only have one tool, it has to be the solution to every problem you encounter. So, I began working on my tool chest to expand the ways I could create intrigue, action, suspense, and just general good writing. That’s when I encountered the Johari window.

The Johari window was advanced in 1955 as a means of better understanding oneself and one’s relationship to others. The name came from the combined first names of its inventors, Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham.

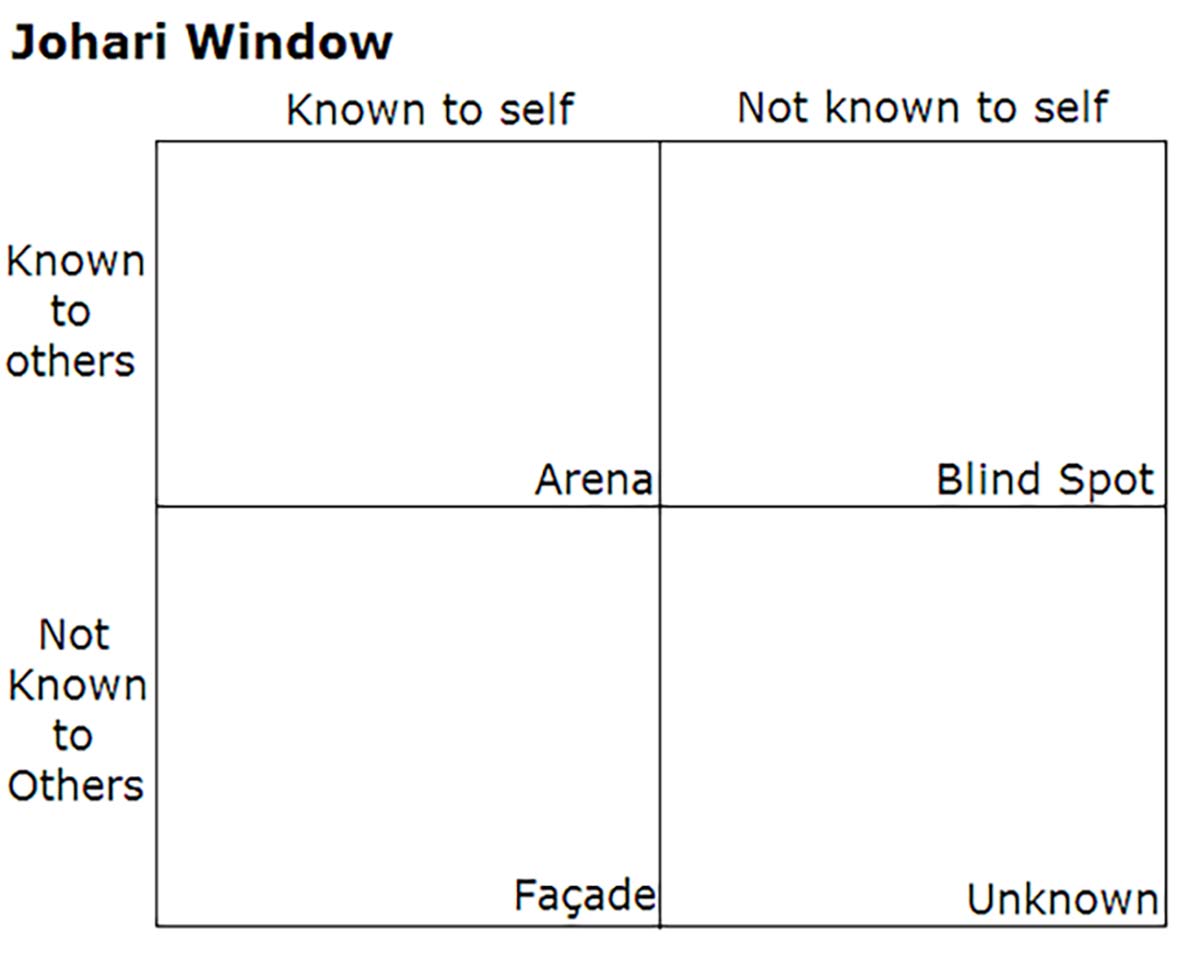

The Johari window is a simple grid of four cells, two across and two down. Across the top the cells are labeled “Known to self” and “Not known to self.” On the left, the cells are labeled “Known to others” and “Not known to others.” The upper left cell, then, is what is known both to oneself and to others. It is common knowledge, also referred to as ‘the arena.’ It is where most social interaction occurs.

The upper right cell is things that are known to others, but not known to oneself. It is the self’s blind spot. The lower left cell is what is not known to others, but is known to oneself. It may be referred to as the façade, or the hidden. The final, lower right cell is the unknown. These are things not known by either the self or others. It is sometimes referred to as the area of discovery.

That seemed to be exactly what the structure of a novel or even a good scene could be. We have protagonist and antagonist and what is known to whom.

I think of a famous scene in the 1994 movie Disclosure with Michael Douglas and Demi Moore. Both Michael and Demi know they are in an office trying to have sex or not have sex. Michael knows this is wrong and is having difficulty communicating it to Demi. Demi knows this is a way to control Michael and ultimately shift blame for plant failure from her to him. What neither of them know is that Michael’s phone is still connected to another person’s voicemail and their encounter is being recorded.

That scene was the first that made me think the Johari window could be used as a technique for plotting a scene. We have what the protagonist knows and doesn’t know, and we have what the antagonist knows and doesn’t know. The action of the scene is in ‘the arena,’ or what both know. But the story lies in the unknown. It contains the big discovery that will bring the story to light.

I used the Johari window technique at critical points of the Team Manager series. For example, in SWISH!, the bad guys know someone is spying on them and they believe it was Dennis’s father. Dennis’s father knows it was some girl who had taken pictures. The action is in that arena. The story, or discovery, however, is it is the sister of one of the bad guys who was spying and taking the pictures.

This concept is repeated in CHAMP! when Dennis is trapped in the coaches’ office as two thugs attempt to sabotage the building. He knows they are there and up to no good. They don’t know he is there. They know they are being paid well to drill holes in the roof. None of them know who is actually paying them to create havoc. Action and discovery, the arena of what both know as they discover what each other knows and the unknown instigator of the attack.

The individual eBooks and entire Team Manager series are available on Bookapy.

While this works well with a well-defined protagonist and antagonist, I’ve also discovered it works in a more general way when I am plotting and writing. I put myself in the picture as the narrator and characters, and you as the reader. There are things that we both know, i.e. what the narration and characters have divulged. There are things the reader knows because the narration has told them, but the characters don’t know. Of course, there are things the narrator knows that the reader doesn’t know because he hasn’t told them yet. And finally, there is the detail of how this is all going to come together to a resolution, which no one knows.

I can’t tell you how often I reach a point in a story where I simply don’t know! But I know where to find out.

Trying to fit every situation into a Johari window is the same as having only a hammer. Many situations don’t work and don’t enlighten the writer. That’s okay. It’s why we have other tools in the big box. We can always have a man with a gun enter the room!

I’ll try to continue the idea of tools next week, but I don’t have a title yet for the post. I’ve been going through papers I wrote many years ago in my Noveling Notes blog, which I have lost access to. There’s a lot of reading to be done.

Please feel free to send comments to the author at devon@devonlayne.com.