8/25/2024

The Beat Goes On

This is number seventy-six in the blog series, “My Life in Erotica.” I encourage you to join my Patreon community to support my writing.

I PROMISED MORE about plotting and story arc in last week’s post, and here I am to deliver. Sort of. With seventy-odd books in the market and two different author names, you would think I should know what I’m talking about. It ain’t always so.

In fact, I get comments from readers who challenge me on nearly every topic that comes up in my books, including my use or avoidance of plots. An excellent and highly respected author sent me a message after reading one of my stories and said, “I struggled to understand what the underlying message of it was, or if there was one at all.”

I was called out! Indeed, any concept of an underlying message was vague if present at all. But I was personally awakened to revitalizing my plotting of stories and doing less of a diary approach to the development of a story.

Even as a double major in college in English and Theatre, I was not taught how to become a famous author. I was taught to analyze and discuss the works of famous authors, but missed the day the professors discussed how to apply that thinking to my own writing.

So, the things I explore in this blog are often things that, at the ripe old age of @%$^&, I’m still struggling with, whether in erotica or mainstream fiction.

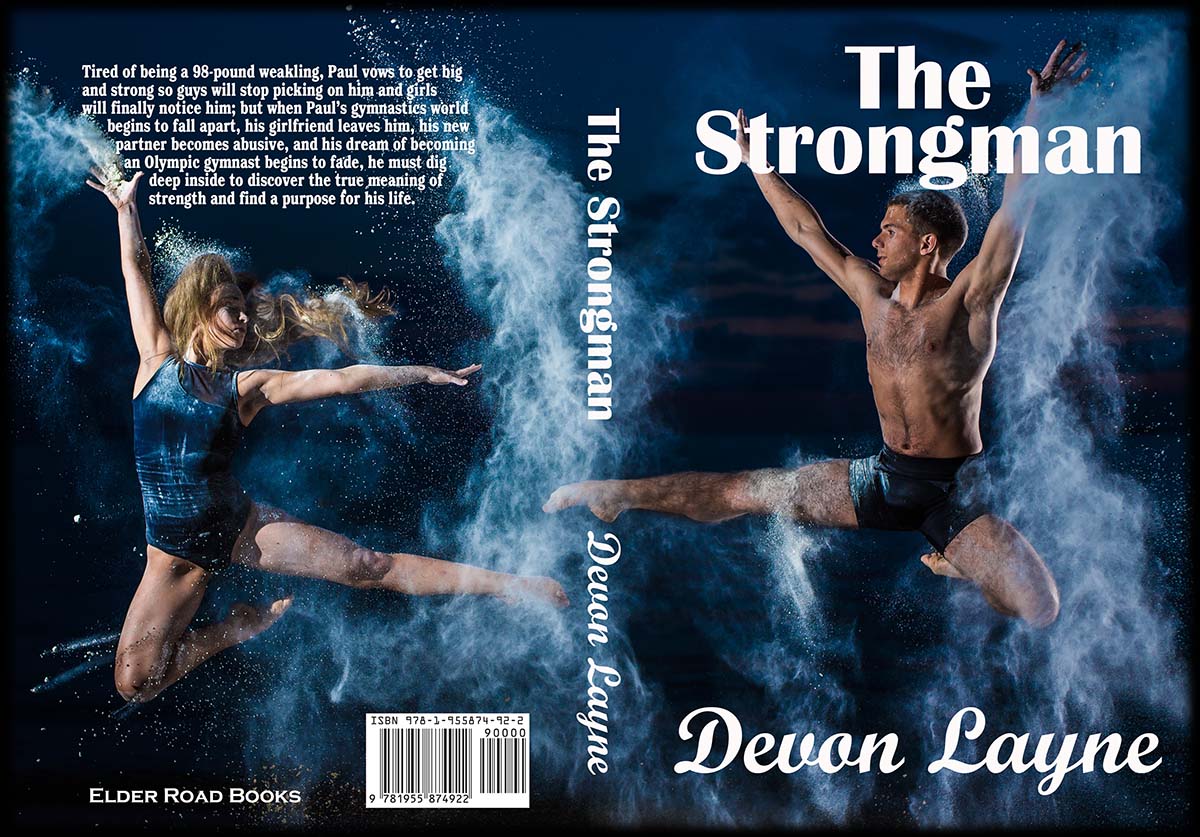

I also mentioned I would discuss the creation of a beat sheet in the context of today’s official release of my newest Devon Layne book, The Strongman.

The first step in creating the beat sheet is to create the logline. A logline is supposed to be a one-sentence description of what the story is all about. In a sentence(!!!) it is supposed to answer the question asked me by the author referred to above. What is the underlying message? In other words, “Why should I read it?”

I’ve found that one-sentence descriptions often end up so convoluted that I’m willing to break them into smaller bites. The idea, though, is to give me the message of the book in as few words as possible. Here it is:

Tired of being a 68-pound weakling, Paul vows to get big and strong so guys will stop picking on him and girls will finally notice him; but when Paul’s gymnastics world begins to fall apart, his girlfriend leaves him, his new partner becomes abusive, and his dream of becoming an Olympic gymnast begins to fade, he must dig deep inside to discover the true meaning of strength and find a purpose for his life.

Okay. That’s what I mean by a single convoluted sentence. Let’s break it down. First, we have the hero’s starting situation. We have his proposed solution. We have the results of getting there. And finally, we have revealed the underlying message. Being strong doesn’t necessarily mean what he thought it did as a child.

The Strongman by Devon Layne has been released this morning (August 25, 2024) in both eBook and paperback at most online bookstores around the world.

This statement guided the writing of The Strongman from the first words on the page to the end of the book. But, of course, it wasn’t quite enough to write the whole story. And so, we get into the beat sheet. Remember the three acts and fifteen beats I alluded to last week? To start, let’s define a beat as a segment of the story that has a clear goal. Beats may overlap or even be re-ordered, but they have a clear goal for moving your story forward. This is where they become the strength of the plot.

Act I

- 1. Opening Image (0% to 1%) – A “before” snapshot of the hero and his or her world.

- 2. Theme Stated (5%) – A statement made by a character that hints at what the hero must learn/discover before the end of the book.

- 3. Setup (1% - 10%) – An exploration of the hero’s status quo life and all its flaws, where we learn what the hero’s life looks like before its epic transformation. Here we also introduce other supporting characters and the hero’s primary goal.

- 4. Catalyst (10%) – An inciting incident (or life-changing event) that happens to the hero, which will catapult them into a new world or new way of thinking.

- 5. Debate (10% to 20%) – A reaction sequence in which the hero debates what they will do next.

Act II

- 6. Break Into 2 (20%) – The moment the hero decides to accept the call to action, leave their comfort zone, try something new, or venture into a new world or new way of thinking.

- 7. B Story (22%) – The introduction of a new character or characters who will ultimately serve to help the hero learn the theme.

- 8. Fun and Games (20% to 50%) – This is where we see the hero in their new world. They’re either loving it or hating it. Succeeding or floundering. Also called the promise of the premise.

- 9. Midpoint (50%) – Literally the middle of the novel, where the Fun and Games culminates in either a false victory or a false defeat. Something should happen here to raise the stakes and push the hero toward real change.

- 10. Bad Guys Close In (50% to 75%) – If the Midpoint was a false victory, this section will be a downward path where things get progressively worse for the hero. The hero’s deep-rooted flaws (or internal bad guys) are closing in.

- 11. All Is Lost (75%) – The lowest point of the novel. An action beat where something happens to the hero that, combined with the internal bad guys, pushes the hero to rock bottom.

- 12. Dark Night of the Soul (75% to 80%) – A reaction beat where the hero takes time to process everything that’s happened thus far. The hero should be worse off than at the start of the novel.

Act III

- 13. Break Into 3 (80%) – The “aha!” moment. The hero realizes what they must to do to not only fix the problems created in Act 2, but more important, fix themself.

- 14. Finale (80% to 99%) – The hero proves they have truly learned the theme and enacts the plan they came up with in the Break Into 3. Not only is the hero’s world saved, but it’s a better place than it was before.

- 15. Final Image (99% to 100%) – A mirror to the Opening Image, this is the “after” snapshot of who the hero is after going through this epic and satisfying transformation.

I credit all the information on the beat sheet to Jessica Brody’s book Save the Cat! Writes a Novel, which was in turn based on Blake Snyder’s screenwriting book, Save the Cat!

Is this information—the story arc created by the beat sheet—sufficient? It’s a great place to start, and I believe The Strongman is a fair representation of a book based on a carefully constructed beat sheet. However, the beat sheet is not a formula for writing, nor is it the only way to approach the problem. After I completed the beat sheet, for example, I went on to create a detailed outline, chapter-by-chapter, that described what was unique about this book. The outline, of course, is where a dedicated author will fill in the details. It’s also where we find differences between the exact structure of the beat sheet and the story arc as it develops. That’s different for every book.

I think I’ll write at least one more blog on the general subject of plotting. Next week, I’d like to compare another famous description of the story arc: Joseph Campbell’s The Hero’s Journey.

Please feel free to send comments to the author at devon@devonlayne.com.